JUNE 28, 2002

SECURITY FOCUS

By Mark Rasch

John Ashcroft's decision to unshackle the FBI's domestic surveillance powers seem perfectly reasonable... if you forget why the bureau was shackled in the first place

Earlier this month, Attorney General Ashcroft announced that he was essentially removing the shackles from the FBI, and permitting agents to engage in surveillance -- including certain Internet surveillance -- of political, social or ethnic groups, without either probable cause or reasonable suspicion that any of these groups had been or were likely to be engaged in any form of criminal activity.

In detailing the changes, FBI Director Mueller explained the FBI guidelines that have previously precluded such conduct applied only to the FBI and not other law enforcement agencies, had no basis in Fourth Amendment or other privacy jurisprudence, were voluntary, and were significantly hampering the ability of FBI agents to gather basic intelligence of the sort that could be gathered by any eleven-year-old with a desktop PC. In this day of terrorism, Ashcroft and Mueller hypothesized, law enforcement must be unshackled to prevent all sorts of criminal activities, and fear not, ye defenders of liberty, for the FBI will continue to monitor itself, and keep itself in check.

The old FBI guidelines emerged in the wake of Watergate-era revelations that the bureau had engaged in extensive surveillance of political and religious groups for unlawful purposes. In 1976 then-attorney general Edward Levi imposed a series of �voluntary� restrictions on the authority of the FBI to engage in surveillance of domestic political groups. Under programs like the FBI's COINTELPRO, the bureau had not only engaged in surveillance of political groups -- agents attended political rallies and maintained dossiers on leaders like Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. -- but they went beyond this and actively disrupting the lives and careers of those it considered to be disloyal to America.

What is important to note is that these activities were all done without any reason to believe that any of these groups or individuals were engaged in any activity that violated any law.

The Levi guidelines -- voluntary only in the sense that they were imposed before Congress could make them mandatory -- stated that investigations of political and religious organizations could be brought only where �specific and articulable facts� indicated criminal activity, and even then, required reporting directly to the Attorney General -- not simply the FBI director. The guidelines were successively weakened by attorneys general Smith and Thornburgh in the Reagan Administration, to permit �preliminary investigations� of such groups if there was a �reasonable indication� of criminal activity.

WEB OF SPIES. With the explosive growth of the Internet, particularly during the Clinton administration, privacy advocates and others (particularly those old enough to remember the COINTELPRO program) were naturally concerned about the FBI's role in �monitoring� the Internet.

It is important to distinguish various kinds of �monitoring� and types of information contained on the Web. At one end of the privacy spectrum are private or personal communications, like e-mail. The interception of such communications requires either a Title III wiretap (which demands a high level of proof to a court that criminal activity is ongoing) or a wiretap order under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), which similarly requires a court order from a special intelligence court, but does not require a showing of criminal activity. For the most part, discussions related to �Carnivore� and �Magic Lantern� focuses on this type of information.

The new guidelines should have little effect on this type of surveillance, since the FBI must at least initiate an investigation and make some showing of probable cause before engaging in this type of spying.

It's the other end of the spectrum where the new guidelines come into play. This is the �public� Internet -- publicly available Web sites, message boards, Web logs and other information that is accessible to anyone online.

The real question is whether the FBI should be permitted to gather intelligence, do profile analysis, and research on information that is publicly available to us all, without having to show that it is doing so for the purpose of investigating some specific criminal activity.

CHILLING EFFECTS. FBI director Mueller correctly points out that the information the bureau will now gather is, essentially, public information. Sure, the FBI could follow me through the streets and ascertain that I went to a meeting of the local chapter of the Chamber of Commerce, or the Libertarian Party, or an EPIC film opening, but these activities occur in either a public or semi-public space.

But this is a red herring. The problem that the Levi guidelines were intended to solve -- and that the new guidelines will exacerbate -- relates to the purpose for which the public information is gathered and utilized, not so much with the privacy of the information itself. Imagine if the FBI routinely monitored rape crisis and awareness postings on Web message boards -- or made false postings themselves -- with no suspicion that the posters were engaged in criminal activity . Imagine that they're doing it solely for the purpose of gathering intelligence.

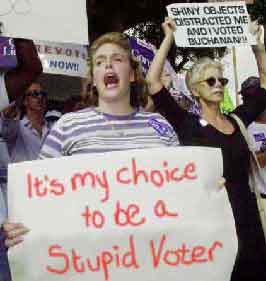

Magnifying the problem is the fact that the intelligence gathering activities may now be directed at political meetings -- particularly unpopular political meetings. Imagine FBI agents taking notes on a pastor's sermon, a rabbi's lecture, a priest's homily -- and noting the names and license plate numbers of attendees. Your �Greenpeace� bumper sticker, publicly displayed, becomes sufficient cause for the FBI to open a file on you.

Privacy is the right to be left alone. Political freedom is the right to engage in vigorous discourse and exploration of ideas -- even unpopular and potentially subversive ideas. We have and should expect a right to privacy even in those things that occur and are reported on in the public. The mere act of the FBI collecting newspaper clippings mentioning our name -- something clearly public -- has a chilling effect on our free discussion. The requirement that they do so only where there is some reason to believe that were are engaged in criminal activity is not unreasonable.

Permitting law enforcement agencies to gather �intelligence� on religious organizations, political groups, or other such associations not only violates the spirit of the Fourth Amendment, but chills speech and association rights as well. Let the FBI investigate crime. Let them not investigate thought.

SecurityFocus Online columnist Mark D. Rasch, J.D., is an independent computer security and privacy consultant in Bethesda, Maryland, and a former attorney with the U.S. Department of Justice Computer Crime Unit.

Design copyright Scars Publications and Design. Copyright of individual pieces remain with the author. All rights reserved. No material may be reprinted without express permission from the author.

Problems with this page? Then deal with it...