Feminism seeks new adherents -- and old goals

By Cathy Young

Manifesta: Young Women, Feminism, and the Future, by Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 416 pages, $15

Sex & Power, by Susan Estrich, New York: Penguin Putnam/Riverhead, 287 pages, $24.95

Flux: Women on Sex, Work, Love, Kids, and Life in a Half-Changed World, by Peggy Orenstein, New York: Doubleday, 325 pages, $25

The heated feminist debates of the early 1990s seem to have simmered down, but the flow of books about the future of women and feminism continues unabated. 1999 was a vintage year for conservative homilies such as Wendy Shalitıs A Return to Modesty and Danielle Crittendenıs What Our Mothers Didnıt Tell Us, both of which argued that the quest for equality had gone too far and urged women to rediscover traditional values. By contrast, the last months of 2000 saw a crop of books proclaiming that feminism has not gone far enough and urging women to complete the revolution. But how to fight, and for what? The new feminist-revival books -- Flux: Women on Sex, Work, Love, Kids, and Life in a Half-Changed World by Peggy Orenstein, Sex & Power by Susan Estrich, and Manifesta: Young Women, Feminism, and the Future by Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards -- may raise more questions than they answer.

Manifesta tackles an issue that has perplexed feminists for some time: defining a feminism that would speak for, and to, the women of post-baby boom generations. The 30-year-old authors, who met while working at Ms. magazine, bristle at claims that young women are indifferent or hostile to feminism. Any woman born in America in the past 35 years, they as-sert, has grown up feminist, taking it for granted that �girls can do anything boys can� (which is largely true, though surely not in every pocket of American life). �For our generation, feminism is like fluoride,� Baumgardner and Richards write, in a striking and insightful analogy. �We scarcely notice that we have it -- itıs simply in the water.�

They want to integrate an essentially personal feminism into a political one and reconnect young women to the womenıs movement: �We need to transform our confidence into a plan for actually attaining womenıs equality.� In their view, young �Third Wave� feminists need to respect the gains won by the �Second Wave� in the 1960s and ı70s, but the elders must also let the young women define �a feminism of their own.�

What does that mean? Well, for one, it affirms female sexuality in all its forms, be it heterosexual monogamy, bisexuality, S&M, or the sexual self-display condemned as exploitative by many Second Wavers (who shuddered at the sight of Madonna in her pre-mommy days or the bra-brandishing �soccer babe� Brandi Chastain). The Manifesta version of Third Wave feminism also happily accepts lipstick, sexy clothing, and high heels, blending female empowerment and �pink-packaged femininity� into a style Baumgardner and Richards call �Girlie� -- which encompasses the Spice Girls, womenıs soccer, the Barbie doll, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

The duoıs chirpy enthusiasm for pop-culture icons and artifacts from Courtney Love to Victoriaıs Secret lingerie to Xena: Warrior Princess can be tiresome, and their writing all too often confirms the very stereotypes of young feminists that they seek to disprove -- namely, silliness and self-absorption. And yet their irreverent young feminism has its appealing aspects.

In one chapter, the authors challenge the still-common notion of epidemic low self-esteem among girls and the portrayal of girls as �victims of society...whether or not they themselves feel this way.� They astutely note that the �girl empowerment� movement often serves less the needs of girls than those of adult activists. They have the temerity to make fun of menstruation-celebrating rituals, and they boldly set out to reclaim the word �girl� in reference to grown women -- as �the female analogue to guy.ı�

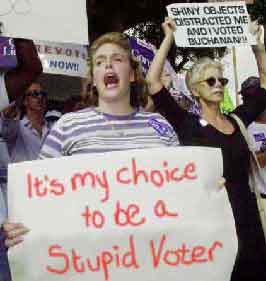

More important, Baumgardner and Richards take an unabashed delight in the vast array of choices American women enjoy today, in matters as serious as childbearing and as frivolous as nail polish. Unlike the prissy Susan Faludi (author of Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women and Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Male), they do not turn up their noses at consumer culture. Instead, they see it as a source of pleasure, and an arena where women freely exercise their preferences. Third Wave feminism is, they assert, all about choice. You can be �a stay-at-home mom, a big Hollywood producer, a beautiful bride all in white,� or �a female cadet at the Citadel.� No problem: �In reality, feminism wants you to be whoever you are -- but with a political consciousness.�

And thereıs the rub: When it comes to sexual orientation, occupation, and lifestyle, the more choice the better. But when it comes to politics, the authorsı respect for diversity evaporates. Baumgardner and Richards never so much as try, as Naomi Wolf half-heartedly did in her 1993 book Fire With Fire, to transcend feminismıs allegiance to the left. Youıre allowed to wear garter belts and wax your legs, but donıt you dare support school vouchers or Social Security privatization. �Right-wing� women -- a category into which the authors lump not only moderate, pro-choice conservatives such as Christina Hoff Sommers but libertarians such as REASON Editor-at-Large Virginia Postrel -- are simply caricatured as enemies of womenıs rights. Their arguments are never even briefly engaged.

When Baumgardner and Richards reveal their actual agenda, itıs mostly boilerplate �feminist� causes: reproductive rights, equal pay for �comparable� work, violence against women, even a dusted-off Equal Rights Amendment. Some worthy issues they want the womenıs movement to tackle, such as draconian sentences for minor drug offenders, surely affect at least as many men as women.

At other times, Manifesta reduces complex issues to simple sloganeering. Welfare reform that steers mothers into the workforce and limits their time on the dole is denounced as anti-woman. The exclusion of women from certain military occupations is assumed to have no practical justification (even though many servicewomen disagree). If the courts give custody of a child to the father after rejecting the motherıs accusations of sexual abuse, helping her abduct the child is treated as an unambiguously noble form of �activist volunteering.� Baumgardner and Richardsı statistics are as sloppy as their thinking. In their discussion of comparable worth, they assert that �accountants are usually male� and are paid more than usually female bookkeepers. In fact, by 1999, more than 58 percent of accountants in the United States were women.

So underneath the hip exterior of Manifesta lurks, mostly, the same old rusty orthodoxy. The book concludes with the authorsı vision of a feminist future -- a sublimely ridiculous utopia in which the federal government not only subsidizes child care, abortion, and �environmentally sound menstrual products� but also regulates salaries at even the smallest companies to enforce comparable worth laws. In this wonderful world, mothers and fathers alike are required to take paid paternity leave, streets are safe for women at any time of the day or night (apparently, come the revolution, not only sex crimes but garden-variety muggings will disappear), and newscasters on television �come in all shapes and sizes.�

The feminism of Manifesta excludes not only everyone who is not a socialist but everyone who deals with feminist issues in everyday life but has no interest in belonging to a movement. The underlying assumption here is that equality can and must be attained only through political activism. On some issues, such as abortion, political action is clearly appropriate and necessary, but the real barriers to womenıs full and equal participation in all spheres of society are of a kind the government can do very little to remedy.

These issues are tackled, in very differ-ent ways, in Sex & Power and Flux. If the Baumgardner-Richards universe is peopled by bohemian activists, journalists, and artists who ponder such questions as whether to call themselves �bisexual� or �omnisexual,� Susan Estrich and Peggy Orenstein write about women with real-world jobs that they struggle to balance with their personal lives.

Neither Estrich, a feminist law professor and Democratic strategist, nor Orenstein, a journalist and author, downplay the existence of sex discrimination. (Estrich may even overplay it: She gives full credence to the 1999 MIT report that claimed to find subtle bias against women faculty, ignoring some persuasive critiques of that report.) Yet both clearly feel that at this point, institutional sex discrimination is not the worst obstacle to womenıs advancement.

Itıs not because of discrimination that, as Estrich notes, women who rise to high-level positions in business and the professions are much more likely than their male peers to have no children. And itıs usually not because of discrimination that many women choose to leave the fast track or not to get on it in the first place.

�We take ourselves out of the running, decide that the prize isnıt worth it, or that the mommy trackı is good enough, better than killing ourselves...while a babysitter tends our children,� Estrich ruefully observes.

Estrich makes the familiar complaint that the ostensibly gender-neutral rules of the workplace are actually designed for people without child-care responsibilities. Women, she asserts, could change the rules if they were willing to harness the power of sisterhood and use the clout they already have in politics and in business. Basically, what she proposes is a mommy track -- flextime, telecommuting, job sharing, etc. -- that would allow not only for merit-based career advancement but also for re-entry into the fast lane.

Sex & Power has some interesting ideas and insights, not only about work and motherhood but also about sexuality in the workplace. Its appeal, however, is limited by Estrichıs almost exclusive concern with ushering more women into the highest strata of political and corporate power. She is convinced that this will benefit all women; indeed, she urges women to pursue such positions even if theyıd rather do something else, because it would be selfish to forego the power they could use to help their sisters -- a novel twist on feminine self-sacrifice. But those who do not automatically assume such a trickle-down effect, as Estrich does, are likely to be put off by her elitist focus.

A bigger problem is Estrichıs evasion of the fact that the accommodations she advocates almost inevitably make women more expensive, less efficient employees. However family-friendly the workplace, as long as some people are willing to focus on work with single-minded devotion, they will likely achieve more (all else being equal) than someone who gives 50 percent.

One obvious solution is to make the division of domestic and parental responsibilities more equal. Estrich dismisses this idea as pie-in-the-sky, but Orenstein sees it as central to further change. Unlike Baumgardner and Richards, who assume that this goal can be achieved by fiat and by hectoring men into doing their share, Orenstein understands that women are part of the problem.

�Men may have to do more, but women also have to let them,� writes Orenstein, who interviewed over 200 women while writing Flux. Most women, she concludes, hold on to maternal control, both out of fear of being labeled a bad mother and out of reluctance to relinquish power. Even career-oriented young women who talk the good talk about shared parenting often quickly reveal that they donıt expect and donıt really want men to be equal partners in child rearing.

�I say Iım pissed off that the men arenıt thinking about [balancing work and family], but the truth is, I donıt imagine my husband...thinking about working part-time,� admits a medical student. �I think of it as being my choice.�

These semi-traditional expectations shape womenıs decisions long before they start shopping for maternity clothes. Many choose careers with lower pay (and often less prestige) but more flexibility. They also seek mates who are �husband material�

in the most unreconstructed sense. One young woman interviewed by Orenstein rejects her devoted boyfriend in part, she sheepishly admits, because of his �limited earning potential� as an art director. Abbey, a sales rep for a comic book publisher, is strongly attached to her identity as a professional woman, yet deep down she wants the option of not working when she has kids -- an option she is nearly certain she wonıt exercise.

Is there anything wrong with this semi-traditionalism, if thatıs what people want? Orenstein makes a strong case that the crazy quilt of old and new norms often leaves women painfully conflicted and guilt-ridden, and contributes to marital tensions. While she wants businesses to make it easier for both sexes to lead balanced lives, she stresses that �there are decisions we [women] can make more consciously...consequences we can understand more fully as we assemble the pieces of our professional and personal dreams.�

Orenstein makes her subjects come alive on the page. The material she includes about her own struggles with her biological clock (complicated by illness) is emotional without being narcissistic. Still, her vision is not free of politically correct blinkers. She is too eager to interpret most young womenıs negative reaction to the thought of being single at age 40 as culturally dictated, rather than motivated by a genuinely felt desire for family. And she gives zero consideration to the ways in which choices may be influenced by nature as well as culture.

Take one couple featured in Flux, Brian and Carrie. After having a baby, Brian took extended parental leave -- but he felt bored and isolated at home, while Carrie started to feel she was missing too much by being at work. So, even though she earned more and loved her work more, Brian returned to his job and she quit hers.

Can one, as Orenstein seems to do, rule out at least the possibility that the failure of this role reversal was caused not only by �the tug of tradition� but by the tug of deeper needs? Itıs not that gender is destiny, or that mothers are universally �hard-wired� to be better suited for child rearing than fathers. But, quite possibly, more women than men are so predisposed and would make such a choice even without cultural pressures.

On the other hand, Orenstein offers a valid counterpoint to those who focus solely on biological sex differences and discount cultural pressures. She is right to ask if things might have turned out differently if Brian hadnıt been bombarded with signals that he was expected to work, and Carrie hadnıt been struggling with the credo that a good mother doesnıt let someone else care for her child.

So what next? It is highly doubtful that we will see a re-energized mass feminist movement, whether based on the youth activist model embraced by Baumgardner and Richards or the Old Girl Network model embraced by Estrich. A discussion of sex roles and male-female relations in our culture will undoubtedly continue; but, to be of any use, this discussion has to include men.

Of the three books, only Flux makes any serious effort to do so. (Estrich is far more concerned with sisterhood than she is about the connections between men and women.) Orenstein is candid about the fact that in our �half-changed world,� men have disadvantages of their own -- such as less freedom to choose a fulfilling but not very lucrative vocation. Still, her primary focus is obviously on women. We learn little of what young men think about their family roles, the cultural expectations they face, or their relationships with women. Male voices could have helped put the womenıs struggles in much fuller perspective.

Barring some major social disruption, men and women will likely continue to muddle through on the way to a more equal world. It will be a much easier ride if we realize that this journey is far more personal than it is political -- and that men and women are making the trip in the same boat.

Contributing Editor Cathy Young (CathyYoung2@cs.com) is the author of Ceasefire!: Why Men and Women Must Join Forces to Achieve True Equality (The Free Press).

Design copyright Scars Publications and Design. Copyright of individual pieces remain with the author. All rights reserved. No material may be reprinted without express permission from the author.

Problems with this page? Then deal with it...